Introduction to Rivers & Streams

White water rafting on the Fraser River in British Columbia (powerofforever, iStockphoto)

White water rafting on the Fraser River in British Columbia (powerofforever, iStockphoto)

How does this align with my curriculum?

Learn about the physical geography, chemistry and ecology of rivers and streams.

Earth is made up of many different ecosystems. The ecosystems on Earth can be divided into two groups. Ecosystems on land are called terrestrial. Ecosystems in water are called aquatic. The two main kinds of aquatic ecosystems are freshwater ecosystems and marine ecosystems.

Freshwater ecosystems can further be divided into lentic ecosystems and lotic ecosystems. This Backgrounder is about lotic ecosystems.

Lotic Ecosystems

Lotic ecosystems are found in flowing bodies of freshwater. The word Lotic comes from the Latin word lotus which means ‘washed’. Lotic ecosystems can be as small as tiny springs and as large as rivers several kilometres wide.

Whatever their size, lotic bodies of water have something in common. They all flow in one direction. Water always flows from the headwaters, which are the source of the river or stream, to the downstream terminus, where the river or stream ends.

Did you know?

Scientifically speaking, all running water is a 'stream'. Even the mighty Mackenzie River is just a big stream. In fact, there is a saying to describe the words we used for streams of different sizes. "You can step over a brook, jump over a creek, wade across a stream, and swim across a river."

Physical Geography

Streams are natural watercourses. They flow over the surface of land in channels. They also drain areas of land. The location, size and speed of a river is determined by several things. These include the availability of water, the size of the channel and the slope of the land. This is why the term ‘river’ includes all kinds of watercourses. These range from the tiniest creeks to Canada’s Mackenzie River. The Mackenzie River is the 10th longest river in the world!

Image - Text Version

Shown are two colour photographs of different sized streams.

The left image shows the curve of a stream about one or two metres wide, running through a park. It is shallow enough that rocks on the river bed are visible.The right image shows a small plane with floats on the bottom, tied to a dock in a river. The river is flat, calm, and so wide it stretches almost to the horizon.

Rivers shape the landscape around them. How they do this depends on the volume of water and the speed of its flow.

Fast-flowing water can erode rock, soil and organic matter. In some cases, a river can carve deep valleys into the rock around it. This often happens near a river’s headwaters.

Slow-moving water can deposit materials like silt and dead plants into a river. This usually happens downstream, near the mouth of the river. The mouth of a river is where it joins up with a lake or an ocean. Deposits at the mouth of a river may create a landform called a delta.

Image - Text Version

Shown is a colour aerial photograph of sediment at the end of a river, fanned out into the ocean.

A green stripe, bordered by beige, winds in an S shape from the bottom edge of the image, through green-coloured land. This is labelled “Horton River.” It empties into a huge, deep blue body of water on the right. This is labelled “Franklin Bay.” There is a large half-circle of beige jutting out into the bay, around the end of the river. The top of the pile is pale beige. Closer to the water the sediment is darker. The outside edge is dark brown. Under the water, a thick stripe of wispy teal indicates the sediment is piled here too. This is labelled “River Delta.”

Rain, melted snow and groundwater all affect how much water flows in a river. The flow of a river can change a lot from season to season and year to year. In Canada, river levels are highest in the spring. This is when flooding happens more often. This is because snow melts but the soil is still frozen. It can’t absorb the extra water. Heavy rains can also cause high water levels and flooding in smaller rivers and streams.

In Canada, low river levels and flows often happen in late summer. This is when precipitation is low. Summer is also when water evaporates more easily and plants use more water. River levels are often low in winter as well. This is because they are covered in ice and precipitation is in the form of snow, not rain.

Drainage Patterns

The area of land that supplies water to a river is called a watershed or a drainage basin. This water may come from rain, melted snow and ice, or groundwater. One river's watershed is separated from the watersheds of neighbouring rivers by higher lands called drainage divides or watershed divides.

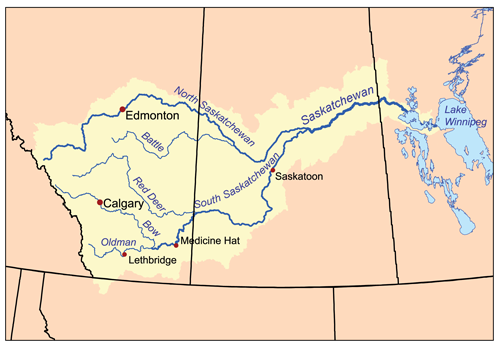

Image - Text Version

Shown is a colour map of winding blue lines, surrounded by yellow areas, across Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

The line begins in Manitoba, at a large pale blue shape labelled “Lake Winnipeg.” It is bordered by pale yellow with irregular edges. The yellow area is fairly narrow as the river winds its way through nearby lakes. Just before the border with Saskatchewan, the yellow area gets much wider. Here, the blue line is labelled “Saskatchewan.” Soon, the blue line divides into two thinner ones. The top one winds northwards. This line is labelled “North Saskatchewan.” The bottom line curves south through a red dot marked “Saskatoon.” This line is labelled “South Saskatchewan.” Now, the yellow area includes all the land between the two new rivers. As the North Saskatchewan River climbs north, an even thinner blue line branches off into the yellow area below it. This is labelled “Battle.” When the South Saskatchewan River crosses the Alberta border, an even thinner line branches off into the yellow area above it. This is labelled “Red Deer.” Further along, another thin line labelled “Bow” winds up to a red dot labelled “Calgary.” Here, the thicker line of South Saskatchewan becomes thinner. This is labelled “Oldman” and leads down through a red dot labelled “Lethbridge.” All the blue lines end just before the jagged border with British Columbia. The yellow area also ends at the border.

Small drainage basins supply water to streams. The drainage basins of several streams often combine to make up the drainage basin of a river. The drainage basins of several rivers combine to make up regional watersheds. These in turn join other regional watersheds to form continental watersheds. These are also known as ocean watersheds.

Rivers in Canada are part of five continental watersheds. The rivers in each continental watershed flow into a different ocean, or another body of saltwater. Rivers in Canada flow into the Pacific Ocean, the Arctic Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, Hudson Bay or Gulf of Mexico.

Image - Text Version

Shown is a map of Canada with different coloured areas divided by white lines. A legend below indicates each colour represents the body of water the region drains into. The multiple shades of each colour represent the regional watersheds.

Starting on the left, most of Yukon and British Columbia is in shades of red. These areas drain into the Pacific Ocean. Shades of orange cover northeast B.C., eastern Yukon, most of the Northwest Territories, and northern Nunavut. These areas drain into the Arctic Ocean. A small sliver of southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, just above the American border, is yellow. This area drains into the Gulf of Mexico. Shades of blue cover the rest of southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, all of Manitoba, southern Nunavut, eastern Northwest Territories, northern Ontario and Québec. These areas drain into Hudson Bay. Shades of green cover southern Ontario and Québec, and all of the Atlantic Provinces. These areas drain into the Atlantic Ocean.

Did you know?

The drainage divide between two continental watersheds is also called a continental divide. These are often marked by road signs. Have you ever seen one of these?

Measuring River Flow

In the spring you might hear an announcement like "Bear Creek is expected to crest later today at 6.3 metres." The 6.3 metres the announcer is referring to is called the stream stage.

Stream stage is the height of the water surface above an established mark which is considered to be zero. The zero level is often close to the stream bottom. The stream stage can be read off a tool called a stream gauge. It can also be recorded electronically by sensors placed in the stream. These send information about the stream stage to a data centre.

Stream stage is important because it can be used to calculate stream flow or discharge. Stream discharge is the volume of water flowing over a point in the stream, over a certain period of time. This is often measured in cubic metres per second (m³/s).

Image - Text Version

Shown is a colour photograph of a white ruler standing up in a stream. The ruler is marked from 0 to 9. The water level is at the 1 mark. The stream is narrow and bordered with green grass. Brown rocks are visible under the clear, gently flowing water.

Discharge and water levels are important. Scientists can use them to manage water resources properly. Here are some of the ways scientists use this information.

- To reduce damage from floods. Scientists can map floodplains. Floodplains are areas near rivers which often flood. They can also create canals to move flood water away from areas they want to protect.

- To design and build structures near rivers. These include bridges, roads and culverts. A culvert is a tunnel that allows water to pass under a road.

- To plan and run environmental programs. This could be related to water quality, fisheries and wildlife habitats.

- To make sure that water resources in Canada are developed in a way that conserves and protects the environment.

Chemistry

Every river has some dissolved minerals. All water has minerals like sodium, chloride, calcium, magnesium and potassium. But how do they get into rivers?

Dust, volcanic gases and natural gases like carbon dioxide, oxygen and nitrogen can combine with water in rain. When toxic materials like sulphur dioxide and lead are in the air, they also become part of rain. When rain reaches the Earth's surface, it flows over and through the soil and rocks. This is called surface runoff.

Image - Text Version

Shown is a colour photograph of a person next to a river, holding a test tube and a laptop.

The person is wearing white, protective overalls, green rubber boots, latex gloves and safety glasses. They are kneeling on the ground, balancing a silver laptop on one knee with one hand. With the other hand, they are holding a clear test tube with grey liquid inside. The riverbed around them is pale grey and gravelly.

As surface runoff flows over land, it can dissolve and pick up materials. If the soil has a lot of limestone, the surface runoff will have a lot of calcium carbonate. This is because limestone is made of calcium carbonate. And calcium carbonate can dissolve in water.

In the Canadian Shield, there are large areas without much soil. These areas don’t have many minerals that dissolve in water either. Because of this, the rivers and lakes in these areas have very low amounts of minerals.

Ecology

Many plants and animals live in or near rivers. Some species are only found in lotic habitats. Some insect species have developed adaptations so they can fight against high currents.

This is the case for blackflies. Blackfly larvae attach themselves to rocks on the river bed. Their mouthparts form a fan shape. They put this into the current to catch microscopic plants and animals to eat.

Image - Text Version

Shown is a colour photograph of a person barely visible in a landscape thick with insects.

The whole photograph is covered in blurred dots. They look beige in the sunlight, against a green hill in the background. They look black against the bright blue sky above. On the left, the outline of a person in a protective suit is barely visible through it all. The glint of a blue stream curves behind their shoulder.

You may have seen salmon swim up rivers. This happens during their spawning season, when they need to lay their eggs. Salmon live most of their lives in the sea. But they always return to the river where they were born. So it’s important to conserve rivers to make sure salmon survive. Sometimes, when a river is blocked by a dam, people build fish ladders to allow salmon to pass over it.

Scientists use many different kinds of organisms to measure the quality of water. These include invertebrates, algae, zooplankton, fish and aquatic macrophytes. Healthy streams have a varied, healthy population of these organisms. If there are not enough organisms, or not enough variety, scientists become concerned.

Benthic invertebrates are a group of bottom-dwelling aquatic animals that don’t have backbones. They live all or most of their lives in the same body of water. And some of them can adapt to pollution. So, if scientists find that a stream only has invertebrates that have adapted to pollution, it could be unhealthy.

Aquatic macrophytes are large plants that grow in or near water. These include cattails, bulrushes and pondweeds. If scientists find there are not enough macrophytes in a stream, it could be a sign of low water quality. If there are too many macrophytes, it could be a sign of too many nutrients in the water.

Image - Text Version

Shown is a colour photograph of a person standing in a river with a net.

The person is bent over, holding a wooden pole with a net on the end. With both hands, they are dipping it into the water flowing around their feet. The person is wearing rubber boots and a green rain jacket and is ankle deep in the river. Brown rocks are visible through the clear water, and leafy green trees on the shore bend down toward the surface.

Learn More

What is a Watershed? (2018)

This video (2:08 min.) by the Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority illustrates how a watershed works and how large they can be.

What is a River Delta? (2023)

This video (1:41 min.) by MooMooMath and Science explains how river deltas form, what they look like, and how they got their name.

Macroinvertebrates and Water Quality (2012)

This video (1:27 min.) by Penn State Public Broadcasting shows scientists finding invertebrates at the bottom of a stream, identifying and counting them.

Why Do Rivers Curve? (2014)

This video (2:56 min.) by MinuteEarth illustrates how rivers change shape, and how they form lakes.

References

Government of Canada. (n. d.) Extent of Canada's wetlands.

Government of Canada. (n. d.) Water and the environment.

Government of Canada. (n. d.) Water quality in Canadian rivers.