SETI - The Search for extraterrestrial Intelligence

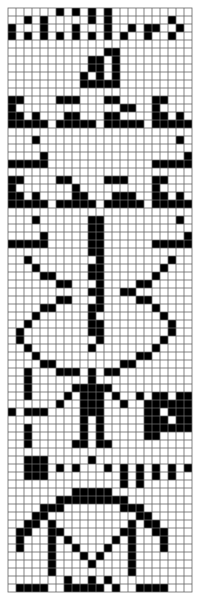

Close-up of the Arecibo Observatory radio telescope (gionnixxx, iStockphoto)

Close-up of the Arecibo Observatory radio telescope (gionnixxx, iStockphoto)

8.5

How does this align with my curriculum?

BC

10

Science Grade 10 (March 2018)

Big Idea: The formation of the universe can be explained by the big bang theory.

BC

11

Earth Sciences 11 (June 2018

Big Idea: Astronomy seeks to explain the origin and interactions of Earth and its solar system.

YT

10

Science Grade 10 (British Columbia, June 2016)

Big Idea: The formation of the universe can be explained by the big bang theory.

YT

11

Earth Sciences 11 (British Columbia, June 2018

Big Idea: Astronomy seeks to explain the origin and interactions of Earth and its solar system.