Clay-Adams Brain

3D representation of a portion of human female brain (Ingenium)

3D representation of a portion of human female brain (Ingenium)

How does this align with my curriculum?

This brain model helped doctors better explain things to their patients. Learn about this Ingenium artifact and make your own version using 3D printing!

These activities are based on artifacts from Ingenium - Canada's Museums of Science and Innovation

Artifact no. 2002.0539.008

This model of a human brain belonged to Dr. Yankoff. He graduated from medical school in 1953. Then he worked as a physician in the Toronto neighbourhood of Leaside.

Dr. Yankoff used the brain model to explain medical conditions to patients who didn’t speak English. It was part of a larger model of a female head and torso.

Visit Ingenium to learn more about this and other artifacts at the Canadian Science and Technology Museum.

A Brief History of Anatomical Models

Medical students learn the structure of the human body by studying anatomy. And the best way to learn anatomy is by dissecting a cadaver. That means taking apart the body of a dead person.

But cadavers have their downsides. They can only be dissected once. They decompose over time. They’re also very rare! Many people do not want their bodies used this way.

That’s why people started making models of the human body. Anatomical models can be used over and over again to teach students. Doctors can also keep them in their offices to help explain medical conditions to patients.

Some of the first anatomical models were made in Japan during the 13th and 14th centuries. These simple models were made out of wood.

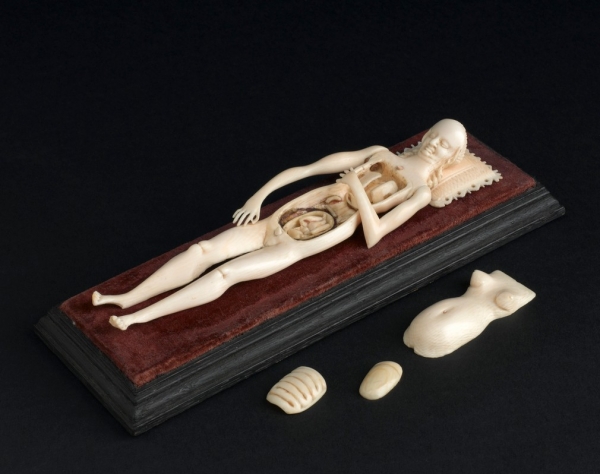

Models made out of ivory became popular in Europe between the 14th and 18th centuries. They were widely used in Germany, France and Italy. Artists carved each model out of a single piece of ivory. The models had removable organs that fit together like puzzle pieces.

In 17th century Italy, people started to make teaching models out of wax. These wax models could be extremely realistic. Wax was better than ivory because it could be coloured to match the colours of an actual human body. It could also show fine details like blood vessels.

But wax models also had a downside. If the temperature got too high, they would melt!

Papier-mâché Models

Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux was a medical student in 19th-century Paris. He noticed that there weren’t enough cadavers for anatomy classes to use. So he started using papier-mâché to create anatomical models. These models became extremely popular! Within a few years, Auzoux made enough money to open his own factory.

Did you know?

Louis Thomas Jérome Auzouz (1797-1880) developed a secret papier-mâché recipe. He used it to make teaching models for medical schools.

Papier-mâché models had many advantages over wax models:

- Unlike wax models, papier-mâché models did not melt.

- Wax models were hand-made one at a time by skilled artists. This was time-consuming and very expensive. But papier-mâché models could be mass-produced. Only the painting had to be done by hand. This also made papier-mâché models much cheaper.

- Some people found wax models too realistic. They would scare patients when doctors used them to explain medical conditions! But the painting on papier-mâché models tended to be simpler and more stylized. This made them easier to look at.

The body parts in papier-mâché models still fit together like puzzle pieces. Doctors and students could easily take them apart and put them back together again. The parts were also labelled.

In North America, medical schools used papier-mâché models from the 1930s to the 1960s. After that, plastic anatomy models became popular.

The Clay-Adams Brain

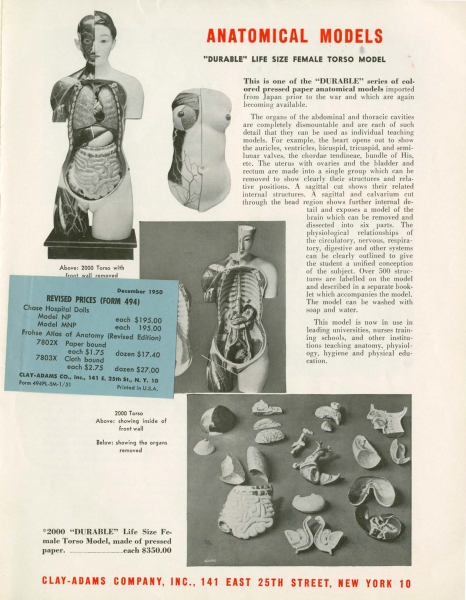

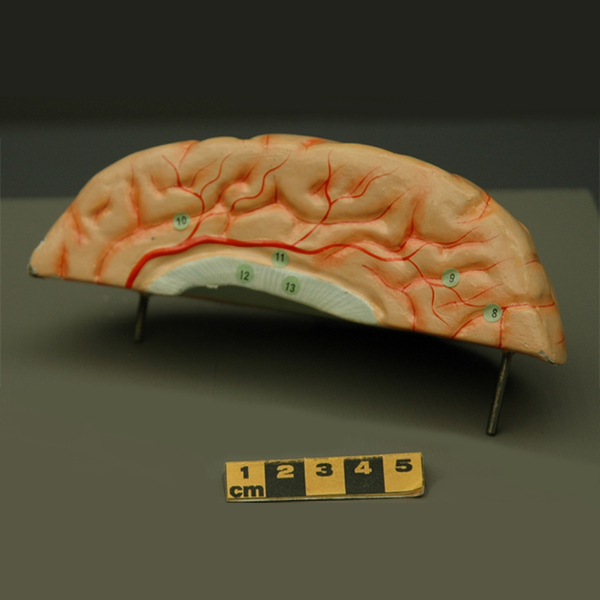

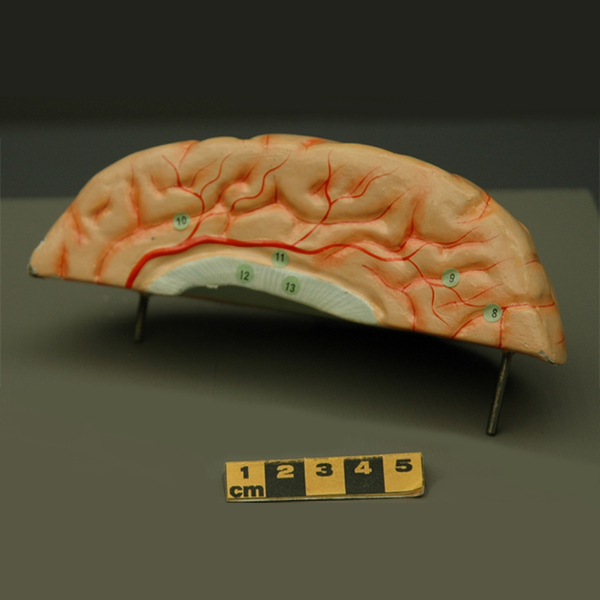

The Clay-Adams brain comes from a life-size model of a female torso. The model was made in the early 1950s by the Clay-Adams Company. It had a wooden frame covered with papier-mâché. The model was durable enough to be handled and it could be cleaned with soap and water.

The model torso had more than 500 organs. Each organ was labelled with a number. This number corresponded to the name of the body part listed in a book.

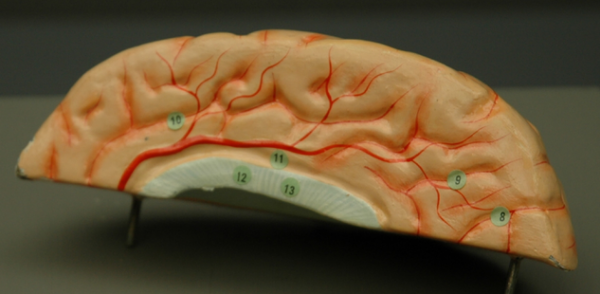

You can see some of these numbers in the picture of the brain model.

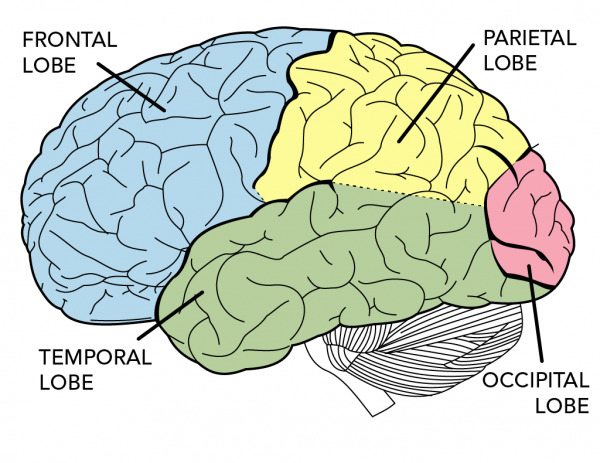

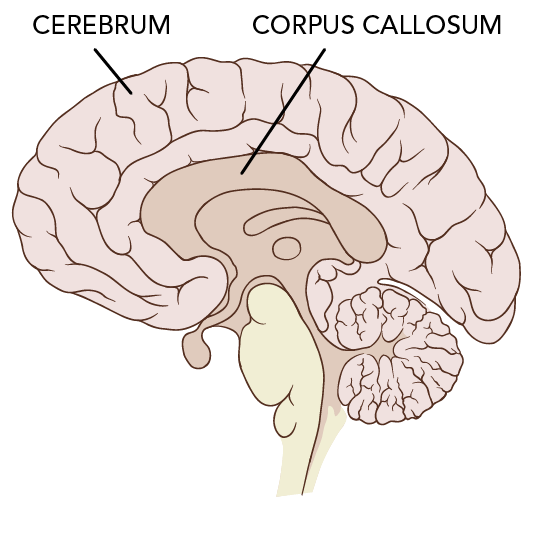

This section of the brain model is the upper front part of the right hemisphere. It shows parts of the frontal lobe and parietal lobe. It also shows parts of the cerebrum and the corpus callosum.

Where would find the frontal lobe? At the front of the brain, of course! It takes care of a lot of important things, like these:

- Critical thinking

- Planning

- Feelings of reward

- Motivation

- Self-identity

- Long-term memory storage

The parietal lobe is located near the back of the brain. It sits behind the frontal lobe and in front of the occipital lobe. The parietal lobe is responsible for sensing proprioception. In other words, it helps you understand the space around your body. It lets you sense things like pain and temperature. It also interprets language.

The corpus callosum is a bridge of nerve fibres that connects the brain’s two hemispheres. It lets the hemispheres communicate, so they can coordinate and synchronize activity.

The cerebrum is the large wrinkly part that covers both hemispheres of the brain. It’s responsible for complex functions and voluntary actions.

These are just a few parts of the brain that Dr. Yankoff could show his patients using a Clay-Adams model!

Starting Points

- Have you ever seen an anatomical model like the ones described in the article? If so, where?

- Do you think wax models are too lifelike? Explain.

- Have you ever made anything out of papier-mâché? What was it? How did you find working with it?

- How and why did the materials used to create anatomical models change over time?

- What role did anatomical models have in teaching medicine?

- Why would an anatomical model be useful for doctors who did not speak the same language as their patients?

- Do you think people should still be dissecting cadavers to learn anatomy or should they use technologies that do not require human bodies, such as virtual reality? Explain.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of each type of material used to make anatomical models (i.e., ivory, wax and papier-mâché)?

- What do you think the numbers represent on the model? Note: no answer key could be located for this model, so make your best predictions and justify based on research.

- Why do you think cadavers are still used today when hands-on models and digital simulations are readily available?

- The video and the 3D files for the Clay-Adams brain model are part of the collection of Ingenium, Canada's science and technology museums. What is the purpose, from the museum’s point of view, of providing access to these types of resources to the general public?

- This article and embedded video can be used to support teaching and learning of Art, Social Sciences, Biology, Anatomy and Technology & Engineering related to 3D printing and the nervous system. Concepts introduced include anatomy, cadavers, dissected, models, ivory, wax, papier-mâché, mass-produced, plastic, right hemisphere, frontal lobe, proprioception and corpus callosum.

- After reading the article and viewing the video, teachers could have students use a Pros & Cons Organizer learning strategy to identify and discuss the positive and negative aspects of using anatomical models for learning anatomy and medicine. Ready-to-use Pros & Cons Organizer BLMs are available for this article in [Google Doc] and [PDF] formats.

- For a hands on follow-up to reading this article, teachers could have students put together virtual papier-mâché body parts using this interactive anatomy model jigsaw from the University of Cambridge (requires Flash player).

- For additional consolidation and hands on application focusing on brain anatomy, teachers could use the STL files to print a 3D model of the brain. Using papier-mâché, students could then create their own brain models by overlaying the papier-mâché mixture over the 3D-printed brain.

Connecting and Relating

- Have you ever seen an anatomical model like the ones described in the article? If so, where?

- Do you think wax models are too lifelike? Explain.

- Have you ever made anything out of papier-mâché? What was it? How did you find working with it?

Historical Significance

- How and why did the materials used to create anatomical models change over time?

Relating Science and Technology to Society and the Environment

- What role did anatomical models have in teaching medicine?

- Why would an anatomical model be useful for doctors who did not speak the same language as their patients?

- Do you think people should still be dissecting cadavers to learn anatomy or should they use technologies that do not require human bodies, such as virtual reality? Explain.

Exploring Concepts

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of each type of material used to make anatomical models (i.e., ivory, wax and papier-mâché)?

- What do you think the numbers represent on the model? Note: no answer key could be located for this model, so make your best predictions and justify based on research.

Nature of Science/Nature of Technology

- Why do you think cadavers are still used today when hands-on models and digital simulations are readily available?

Media Literacy

- The video and the 3D files for the Clay-Adams brain model are part of the collection of Ingenium, Canada's science and technology museums. What is the purpose, from the museum’s point of view, of providing access to these types of resources to the general public?

Teaching Suggestions

- This article and embedded video can be used to support teaching and learning of Art, Social Sciences, Biology, Anatomy and Technology & Engineering related to 3D printing and the nervous system. Concepts introduced include anatomy, cadavers, dissected, models, ivory, wax, papier-mâché, mass-produced, plastic, right hemisphere, frontal lobe, proprioception and corpus callosum.

- After reading the article and viewing the video, teachers could have students use a Pros & Cons Organizer learning strategy to identify and discuss the positive and negative aspects of using anatomical models for learning anatomy and medicine. Ready-to-use Pros & Cons Organizer BLMs are available for this article in [Google Doc] and [PDF] formats.

- For a hands on follow-up to reading this article, teachers could have students put together virtual papier-mâché body parts using this interactive anatomy model jigsaw from the University of Cambridge (requires Flash player).

- For additional consolidation and hands on application focusing on brain anatomy, teachers could use the STL files to print a 3D model of the brain. Using papier-mâché, students could then create their own brain models by overlaying the papier-mâché mixture over the 3D-printed brain.

Learn More

Artificial Anatomy: Papier-Mâché Anatomical Models

An online version of an exhibition at the Smithsonian Natural Museum of American History on this topic, including the history and photos of numerous body parts. (Note: view the Collection section, not the Body Parts section.)

BodyWorlds is a website of the famous traveling exhibition, including history, the plastination technique and information about current and future exhibitions!

Brain Architecture (2015)

Overview of the parts and functions of different areas of the brain from Let’s Talk Science.

References

Case Western Reserve University. (2017, October 26). Paper woman: Auzoux's anatomical models.

Maerker, A. (2008). Dr. Auzoux's papier-mâché models. University of Cambridge.

Markovic, D., & Marković-Živković, B. (2010, January). Development of anatomical models - Chronology. Acta Medica Medianae.

Med Shop. (2017, September 20). The bizarre history of anatomical medical models.

Northeastern University Digital Repository. (n.d.). Company flier advertising anatomical models.

University of Melbourne. (n.d.). Models and Methods.