Earth Month: Climate Change

Flooding in Davenport, Iowa (Kelly Sikkema, Unsplash)

Flooding in Davenport, Iowa (Kelly Sikkema, Unsplash)

7.8

How does this align with my curriculum?

NU

11

Science 24 (Alberta, 2003, Updated 2014)

Unit B: Understanding Common Energy Conversion Systems

ON

11

Environmental Science, Grade 11, University/College (SVN3M)

Strand B: Scientific solutions to Contemporary environmental Challenges

NT

11

Science 24 (Alberta, 2003, Updated 2014)

Unit B: Understanding Common Energy Conversion Systems

AB

5

Science 5 (2023)

Energy: Understandings of the physical world are deepened by investigating matter and energy.

AB

6

Science 6 (2023)

Energy: Understandings of the physical world are deepened by investigating matter and energy.

AB

10

Knowledge and Employability Science 10-4 (2006)

Unit D: Investigating Matter and Energy in Environmental Systems

AB

10

Science 14 (2003, Updated 2014)

Unit D: Investigating Matter and Energy in Environmental Systems

BC

9

Science Grade 9 (June 2016)

Big Idea: The biosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere are interconnected, as matter cycles and energy flows through them.

BC

11

Environmental Science 11 (June 2018)

Big Idea: Changing ecosystems are maintained by natural processes.

NU

10

Knowledge and Employability Science 10-4 (2006)

Unit D: Investigating Matter and Energy in Environmental Systems

NU

10

Science 14 (2003, Updated 2014)

Unit D: Investigating Matter and Energy in Environmental Systems

YT

11

Environmental Science 11 (British Columbia, June 2018)

Big Idea: Changing ecosystems are maintained by natural processes.

YT

9

Science Grade 9 (British Columbia, June 2016)

Big Idea: The biosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere are interconnected, as matter cycles and energy flows through them.

NT

10

Knowledge and Employability Science 10-4 (Alberta, 2006)

Unit D: Investigating Matter and Energy in Environmental Systems

NT

10

Science 14 (Alberta, 2003, Updated 2014)

Unit D: Investigating Matter and Energy in Environmental Systems

BC

11

Earth Sciences 11 (June 2018

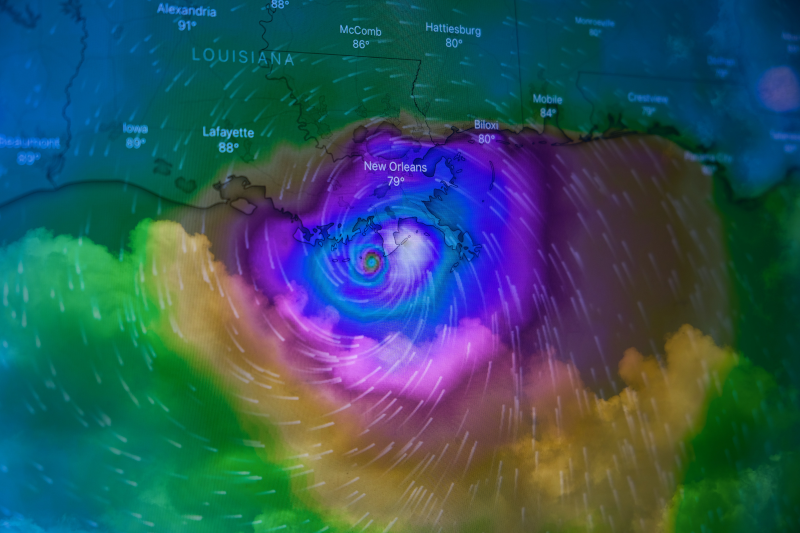

Big Idea: The transfer of energy through the atmosphere creates weather and is affected by climate change.

BC

11

Science for Citizens 11 (June 2018)

Big Idea: Scientific understanding enables humans to respond and adapt to changes locally and globally.

BC

12

Environmental Science 12 (June 2018)

Big Idea: Human activities cause changes in the global climate system.

NS

8

Science Grade 8 (2020)

Learners will evaluate oceanographic and other evidence of climate change inclusive of a Mi’kmaw perspective.

YT

11

Earth Sciences 11 (British Columbia, June 2018

Big Idea: The transfer of energy through the atmosphere creates weather and is affected by climate change.

YT

12

Environmental Science 12 (British Columbia, June 2018)

Big Idea: Human activities cause changes in the global climate system.

YT

11

Science for Citizens 11 (British Columbia, June 2018)

Big Idea: Scientific understanding enables humans to respond and adapt to changes locally and globally.

AB

5

Science 5 (2023)

Earth Systems: Understandings of the living world, Earth, and space are deepened by investigating natural systems and their interactions.

AB

6

Science 6 (2023)

Earth Systems: Understandings of the living world, Earth, and space are deepened by investigating natural systems and their interactions.